Learned Helplessness

What is the connection between the publicized increasing rates of burnout among the population, the inability of Gen Z to get jobs, driver’s licenses, move out of the house, etc. and the state known as learned helplessness? Why try at all if nothing will change? Work is too difficult for a person who has been conditioned into learned helplessness, and it’s futile against what is perceived as a failing economy, mountain of debt, and the coming “climate disaster.” “Dooming” and “blackpilling” tempt a person into helplessness.

Learned helplessness is a state induced by repeated defeat, where a person begins to believe that, no matter what they do, there is no solution to their problem. Prolonged exposure to situations that appear to be impossible to overcome shifts a person’s nervous system for active agency to passive resignation. This is an adaptive mechanism meant to preserve energy, but it also connects to the hormonal and metabolic state of the body. When energy is low a person will perceive fewer possibilities for action, and the helplessness is reinforced.

The phenomenon was discovered through a series of animal experiments in the mid 1900’s. In one experiment, researchers compared the response of rats held under water or placed in a barrel of water. The rats that were confined under the water with their motion restricted and their agency gone where much quicker to stop struggling when compared the the rats in the barrel of water, who presumably felt that there was a possibility of escape.

In the early 1960’s, Richard Solomon and his students at the University of Pennsylvania conducted an experiment with dogs where they restrained dogs in hammocks and shocked their back paws while a pitch played. A day later they placed the dogs in a shuttlebox where they intended for them to escape by jumping across a short barrier. The dogs were supposed to hear the pitch, remember the shock they’d experienced, and escape. Instead the dogs remained in the box, waiting out the shocks. This the researchers understood as a kind of helplessness.

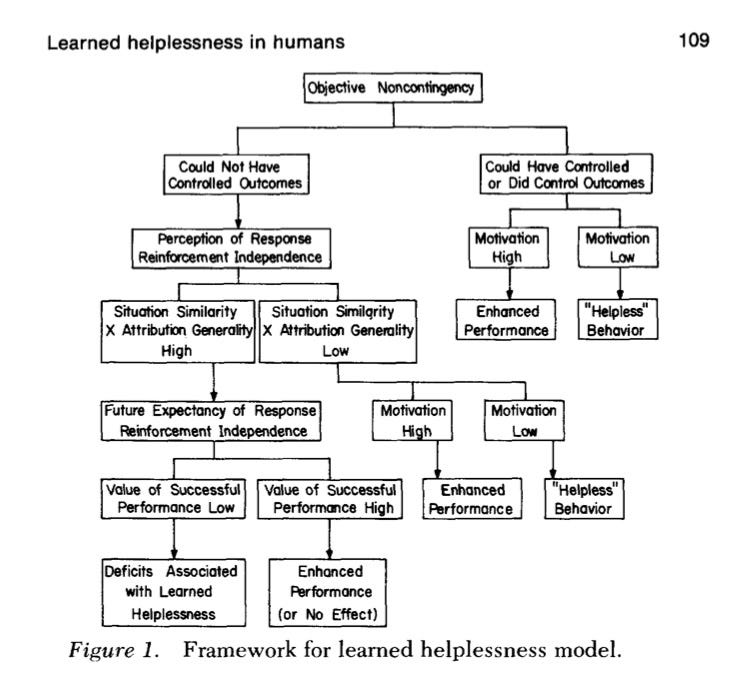

The hallmark of this kind of helplessness is the belief, conscious or unconscious, that nothing one does really matters or makes a difference. This then devolves into what researchers classify as objective and subjective helplessness. Being objectively helpless means that one feels unable to change the outcome regardless of the action taken. To be subjectively helpless is to detect the lack of contingency and expect that in the future nothing can be done to change an outcome. This is learned helplessness, now a conditioned state.

To test this theory, a researcher named Seligman conducted an experiment was conducted on college students. Like the dogs, one group of students were subjected to loud noises that could only be escaped by pressing a button, one was restrained, and one received nothing. Like the dogs, the group that had been yoked failed to escape, while those in the other two groups were able to.

In further research Seligman found that those who attributed their helplessness to permanent causes demonstrated long-term helplessness, while those who attributed it to temporary causes did not show long-term helplessness. If they thought that most or all problems were unsolvable they would exhibit passivity across the spectrum, while if they thought that only some were they would demonstrate passivity only in the original situation.

The third thing that Seligman wanted to know was how this behavior mapped onto the symptoms of depression. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association Third Edition (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980), and Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), major depressive disorder was diagnosed by the presence of at least 5 of the following 9 symptoms:

Sad mood

Loss of interest

Weight loss

Sleep problems

Psychomotor problems

Fatigue

Worthlessness

Indecisiveness or poor concentration

Thoughts of suicide

Combining the animal and human results of the observed learned helplessness produced 8 out of the 9 symptoms, the only exception being suicidal thoughts. Further, those clinically diagnosed with depression who had not experienced inescapable events, when brought into the laboratory, acted as though they had, demonstrating passivity and giving up on cognitive problems.

Something I found interesting while researching this topic was one paper that explained the difference in learned helplessness between people who are type A (those who attempt to exert a large amount of control over their environment) and type B (those who are more moderate.) What they found was that the type A group did not succumb to learned helplessness under moderate stress, folded under high stress, while the type B group was the opposite. This is likely because of a larger effort and subsequent larger failure on the part of the type A person to solve the problem. So a high achieving person who attempts to exert a lot of control over various factors in their life can withstand moderate stress, but not high stress, which renders them helpless. Where the type B has a more relaxed approach to life: helpless under moderate stress but taking action under high stress.

The only way out of learned helplessness is to accept agency; to choose to move out of the situation. I think this solution to learned helplessness may explain in part the popularity of figures such as Jordan Peterson (and the ubiquity of self-help books) as people are searching for a way out of the helpless situation, somewhat like the rats struggling in the barrel of water. Jordan Peterson tells you to clean your room, and that at least is something you can do. The feeling of accomplishment and reward subsequently helps a person escape helplessness, step by step.

Dr. Raymond Peat’s work very intentionally does something similar. In the face of a terrible environment, his work gives one actionable steps to change their physiological state into something better, directly breaking the loop of learned helplessness. The established medical system facilitates helplessness: encouraging reliance on experts, giving drugs with awful side effects, and limiting possibilities. Ray Peat on the other hand empowers the person with the truth that “Living is development. The choices we make create our individuality.” Restoring proper oxidative metabolism, (which is a choice to change one’s diet, lifestyle, etc.) can be a powerful tool for lifting a person out of learned helplessness.

What contributes to learned helplessness?

Noise: A laboratory based study with university students showed that “babble” (such as the noise common in a public space) and “broadband noise” (such as the noise typical of that in an aircraft cabin) can lean to learned helplessness: decreasing motivation and affecting performance. “Babble” noise was worse than “broadband.” I thought this was interesting, because I feel that a lot of our environment is filled with noise, as well as the choice of many to fill their environment with “babble.”

Isolation: One study measured the difference in a learned helplessness response between introverts and extroverts. What they found was that the introverts had much more of a learned helplessness response than the extroverts. Ray Peat reached a similar conclusion from mice studies, that mice that have been isolated are more prone to learned helplessness.

Subjection to meaningless processes: “Possibly the most toxic component of our environment is the way the society has been designed, to eliminate meaningful choices for most people. In the experiment of Freund, et al., some mice became more exploratory because of the choices they made, while others' lives became more routinized and limited. Our culture reinforces routinized living.” -Ray Peat

High stress: stress activates the cholinergic system and begins the hormonal process that helps condition learned helplessness.

What combats learned helplessness?

An interesting and enriching environment: One experiment compared the response of mice that were kept in isolation to mice that were kept in an enriched environment with other mice. The mice that were isolated died quickly, while those that were kept with other mice struggled and resisted effectively. Ray Peat writes that “Enrichment and deprivation have very clear biological meaning, and one is the negation of the other.”

Anticholinergic substances

(such as progesterone, bright light, DHEA, etc.) These substances counter the brain-damaging effects of shock and stress, helping to restore proper recovery without the helplessness response.

Maintaining or restoring respiratory energy production:

Anecdotal and other evidence suggests that proper thyroid function and energy production is able to break a person out of the state of learned helplessness. Ray Peat uses the examples of altitude as something that can restore the brain. “During the development of learned helplessness, the T3 level in the blood decreases (Helmreich, et al., 2006), and removal of the thyroid gland creates the "escape deficit," while supplementing with thyroid hormone before exposing the animal to inescapable shock prevents its development (Levine, et al., 1990). After learned helplessness has been created in rats, supplementing with T3 reverses it (Massol, et al., 1987, 1988).”

-A sense of meaning and purpose:

“It is the basic premise of the learned helplessness model proposed here that people will be more likely to act on their environment the higher the value of potential reward and the higher the perceived probability of obtaining it.” -Ray Peat

Sources:

(Non-comprehensive)

https://raypeat.com/articles/articles/dark-side-of-stress-learned-helplessness.shtml

ROLE OF EXTRAVERSION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF LEARNED HELPLESSNESS, MARIKA TIGGEMANN, School of Social Sciences, The Flinders University of South Australia. Bedford Park, South Australia 5042 and ANTHONY H. WINEFIELD and JOHN BREBNER, Department of Psychology, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide. South Australia 5001

A revised model of learned helplessness in humans, Susan Roth, Duke University

Understanding and Combating Helplessnes, Jill Conwill, MSN RN CETN

Learned Helplessness: A Piece of the Burnout Puzzle, JOHN G. GREER CHRIS E. WETHERED